Source: Stephen Davies Transcription, authenticity and performance (1988)

- A transcription must be intended as such

- Transcriptions are transcriptions of musical works and the contents of the original preserved in the different medium of the transcription are its musical contents

- The aim of the transcription is to faithfully re-create the original work

- A transcription seeks to reconcile the musical content of the original work with the limitations and advantages of a medium for which that content was not designed

- A transcription must depart far enough from the original to count as a distinct piece

- A transcription might alter notes of the originals, if the alterations recreates equivalent configurations

Unknow: Les Sylphide (Chopin) (“they are so faithful to the originals”)

Stravinsky’s Pulcinell (Pergolesi and others) (“Stravinsky […] adds to it […] with a light touch […] to add an ‘edge’ to the sound […] Pulcinella has a Stravinsky-like sound […] the work is more like a transcription than anything else […]”)

Tchaikovsky: Suite No. 4, Op. 61 (transcribes music by (or attributed to) Mozart) (“the orchestration is as much Tchaikovskian as Mozartian” (nb. kind of the same argument that made Pulcinella a successful transcription))

Transcriptions for pedagogical use: exercises in the handling of musical materials (Bach & Mozart’s transcriptions of Vivaldi)

Transcriptions giving access: making the musical contents of their models more accessible (e.g. piano reductions)

Transcripts showing virtuosity: showing the transcribers compositional skill in adapting the musical contents for a new medium (no examples)

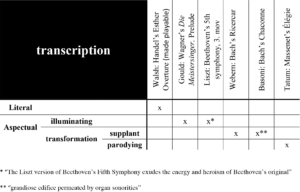

Transcriptions for reflections: enriching our understanding and appreciation of the merits (and demerits) of their models (Busoni and Brahms transcription of Bach’s Chaconne)

Source: Paul Thom’s The Musician as interpreter (2007)

- A transcription is an intentional and experiential representation of its original, that are reflecting certain global features of the original work

- A transcription takes a complete musical work that specifies one medium and substitutes the specification of a different medium

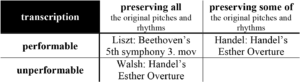

- The content of the transcription is the same as that of the original work. A transcription may preserve the original pitches and rhythms, but preservation of the original pitches and rhythms is neither necessary nor sufficient for a transcription’s success

- the transcriber must find a criterion to maximize the recognizable preservation of the model’s content that does not conflict with playability in the new medium.

- The mapping of the original work’s parts may be selective (this statement seems to contradict 1.-4. above)

Literal transcription shows no particular treatment of its model’s contents (e.g. piano reductions) – Thom’s offers no name for the category, “literal” is my suggestion.

Aspectual transcriptions is designed to reflect upon the original transcribed, representing it as something or other

Illuminating transcriptions cohere with the original work’s features as it support and strengthen the original work’s aims

Transformation transcriptionsis internally coherent but it do not cohere with all of the original work’s features and do not support that work’s aims

I. supplant do not implicitly commenting on the original work

II. parodying do comment on the original work

Source: Richard Beaudoin and Joseph Moore Conceiving Musical Transdialection (2010)

Notational transcription is renotating a musical work (e.g. tablature to staff notation). It aims to preserve a musical work across some difference in notational form, and it can be carried off without listening to the work itself

Ethnomusicological transcription is the process of writing down or notating music that is heard in live performance or on a recording. It aims to preserve music in a notated form.

Musical transcription (sometimes named ‘arrangement,’ ‘setting,’ ‘orchestration,’ and ‘reduction’)

- aims to preserve a specific, preexisting work in its entirety across a difference in performance-means – as when Busoni reset Bach’s organ chorale preludes for the piano

- must at least preserve the expressive content of the original

- must be faithful to the parent work while also providing the audience with something original

Busoni: Bach’s Komm, Gott, Schöpfer, heiliger Geist; “straight” from organ to piano transcription, the numerous octaves, not present in Bach’s score, is to emulate the sound of the organ, Busoni has not changed the fundamental harmonic or melodic content, but he had to make some slight musical changes to preserve the experience of playing and hearing Bach’s work.

Webern: Bach’s six-part Ricercar; The original lines are all preserved, but every line is broken up into small units played by different instrument – a “Webernization” of Bach, and a faithful reexpression of Bach’s work.

Transdialectical transcription

- aims to preserve a specific, preexisting work in its entirety across a difference in musical dialect.

- must at least preserve the expressive content of the original

- must be faithful to the parent work while also providing the audience with something original

Stravinsky: Bach’s Von himmel hoch da komm’ ich her; It’s not a musically faithful transcription. Stravinsky adds some notes on his own that are foreign to Bach’s musical language. He provides a new palette of harmonic and timbral sensitivities within which he endeavors to reexpress Bach’s original music.

Friedman: Bach’s Gavotte, en Rondeau; Friedman adds a thoroughgoing accompaniment to Bach’s monophonie composition. Most the accompaniment invokes Bachian harmonies to support Bach’s line; but in mm. 48-55 it’s a modern chromatic harmony foreign to Bach’s language. Freidman’s transcription preserves the totality of Bach’s original, while adding an accompaniment in Friedman’s own musical style. He reexpresses Bach’s original in an early twentieth-century voice.

Finnissy: Bach’s Deathbed Chorale; in Finnissy’s transcription the rhythms, pitches, and location of the voices are distorted, and he adds new material. Finnissy’s aim is to reexpress Bach’s original in his own twentieth-century musical language. Finnissy’s general musical style traffics in the overlaying, the clashing, and the ultimate destruction of fixed perspective. The transcription brings a new insight to Bach’s original.

Finnissy transdialectical fidelity exemplified:

Mood; the original is profoundly melancholic, lacking climax point and shift in dynamics, the transcription is legatissimmo, sostenuto, intimamente, with dynamics never going above pianississimo

Musical texture; both the original and the transcription is a four-voice counterpoint that winnows to a single voice, then works its way back to four voices, only to oscillate back again

Complexity; the original is of extreme contrapuntal complexity using vorimitation, augmentation, and inversion, the transcription uses extreme rhythmic complexity and atonal harmonies typical for high-modernist.